We’ve often featured the work of the Public Domain Review here on Open Culture, and also various searchable copyright-free image databases that have arisen over the years. It makes sense that those two worlds would collide, and now they’ve done so in the form of the just-launched Public Domain Image Archive (PDIA). The Public Domain Review invites us to use the site to “explore our hand-picked collection of 10,046 out-of-copyright works, free for all to browse, download, and reuse” — and note that the number will grow, given that “this is a living database with new images added every week.”

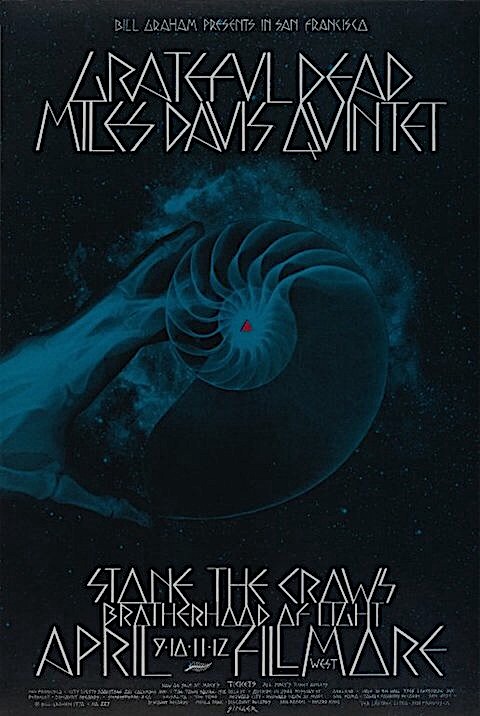

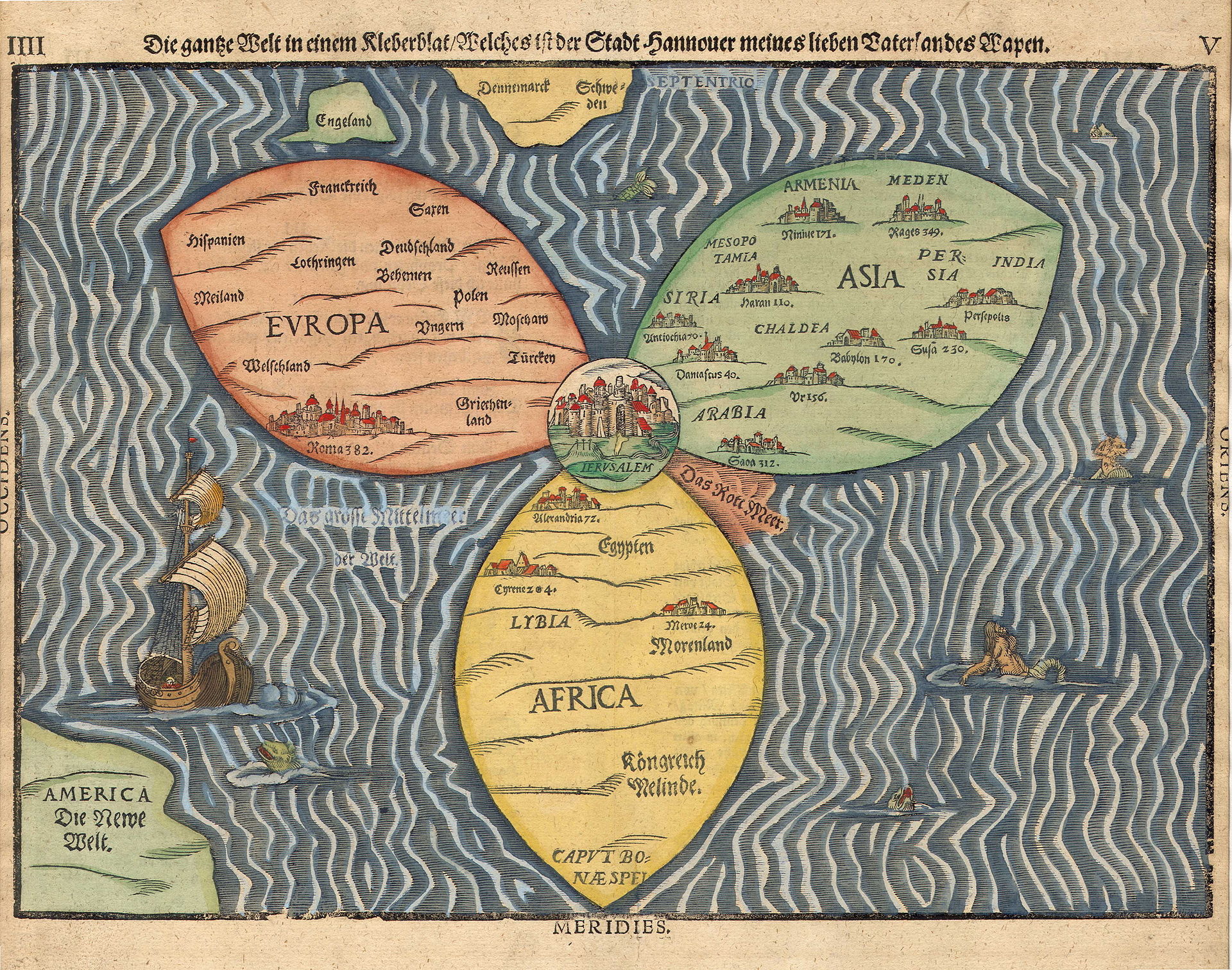

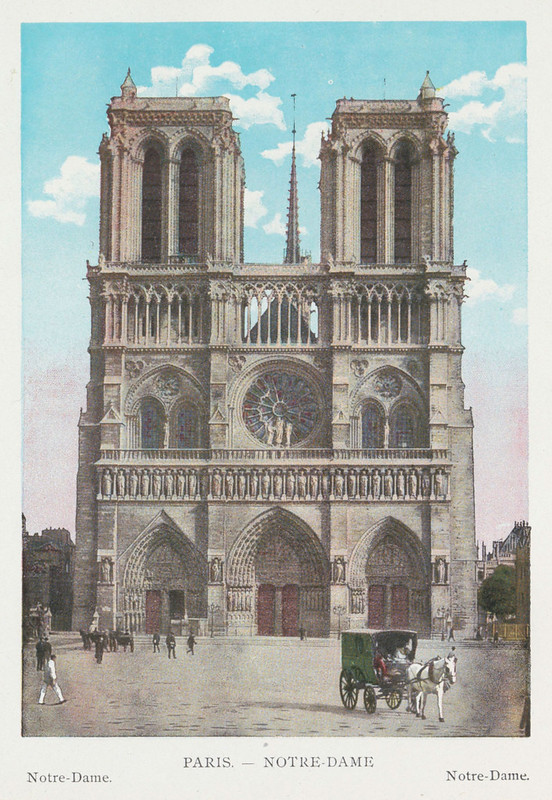

As with any portal of this kind, you can browse by category tags, the selection of which includes everything from architecture to decorations to occultism to war. But if you’d like to get a sense of the sheer formal, aesthetic, cultural, and historical variety of the PDIA, you might consider taking a first look through its “infinite view,” which allows you to scroll in all directions through a limitless labyrinth of copyright-free wonders: advertisements, Biblical scenes, old-time sportsmen, outer-space photos, mushrooms, medieval musical creatures, letterforms, and, well, labyrinths.

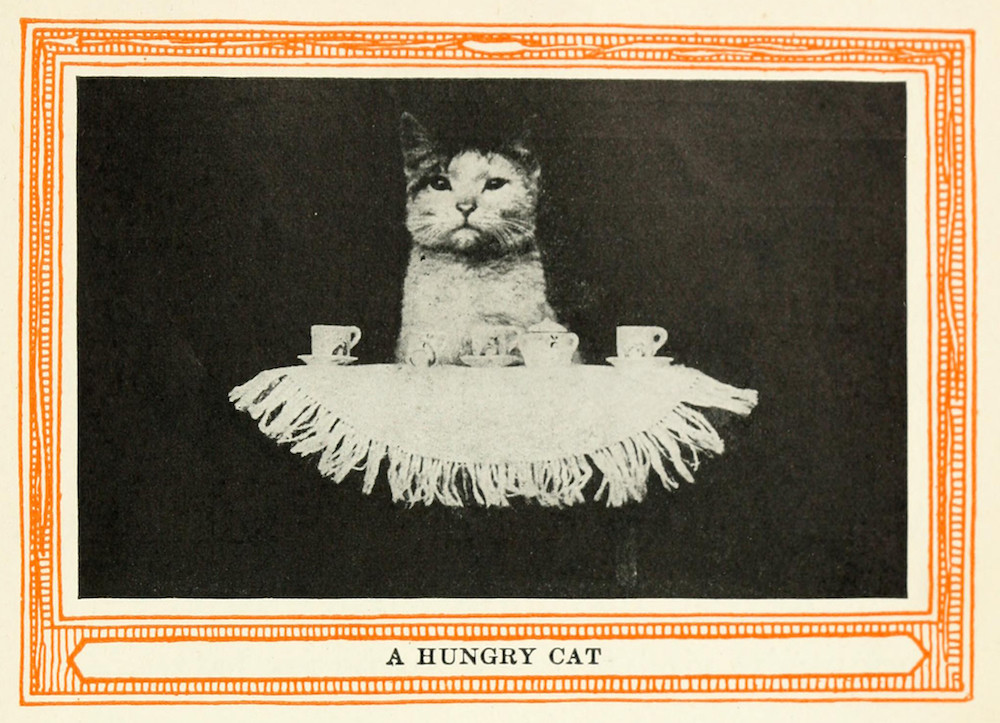

You might also recognize items you’ve seen here on Open Culture before, like the nature drawings of Ernst Haeckel, the modern art-lampooning children’s book The Cubies’ ABC, or the ghosts and monsters illustrated by ukiyo‑e master Hokusai. The PDIA provides more context than some public-domain image archives, even linking to relevant Public Domain Review posts, where you can read about such topics as Emily Noyes Vanderpoel’s color analysis charts (which also inspired a post of ours), the end of books (as predicted in 1894), and even “Cats and Captions before the Internet Age.” Having fallen into the public domain, all this material is, of course, available to use for any purpose you like — including just satisfying your own curiosity.

Related comments:

A Search Engine for Finding Free, Public Domain Images from World-Class Museums

Public.Work: A Smoothly Searchable Archive of 100,000+ “Copyright-Free” Images

Sea-Serpents, Vampires, Pirates & More: The Public Domain Review’s Second Book of Essays

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.